The commentary by Dr Mateusz Piątkowski (Department of Public International Law and International Relations, Faculty of Law and Administration) on the situation between Venezuela and Guyana in the light of international law.

Sources of the territorial dispute between Guyana and Venezuela

The territorial dispute between Guyana and Venezuela dates back to South America's struggle for independence. In 1815, under an agreement with Great Britain, Guyana was ceded to London by the Netherlands.

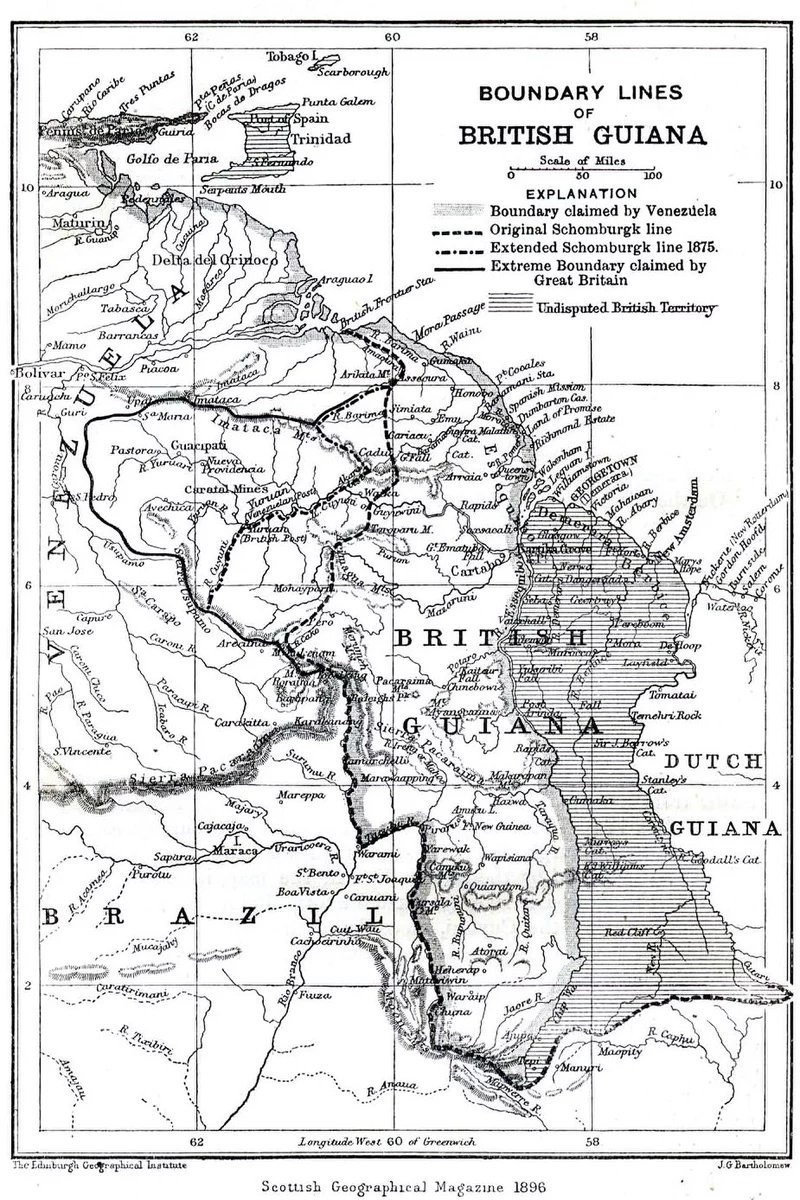

However, the agreement established only Guyana's eastern border, leaving the question of the western border with Venezuela open. In 1835, the Schomburger expedition established the course of the frontier, well beyond the extent of actual British occupation up to the Orinoco River.

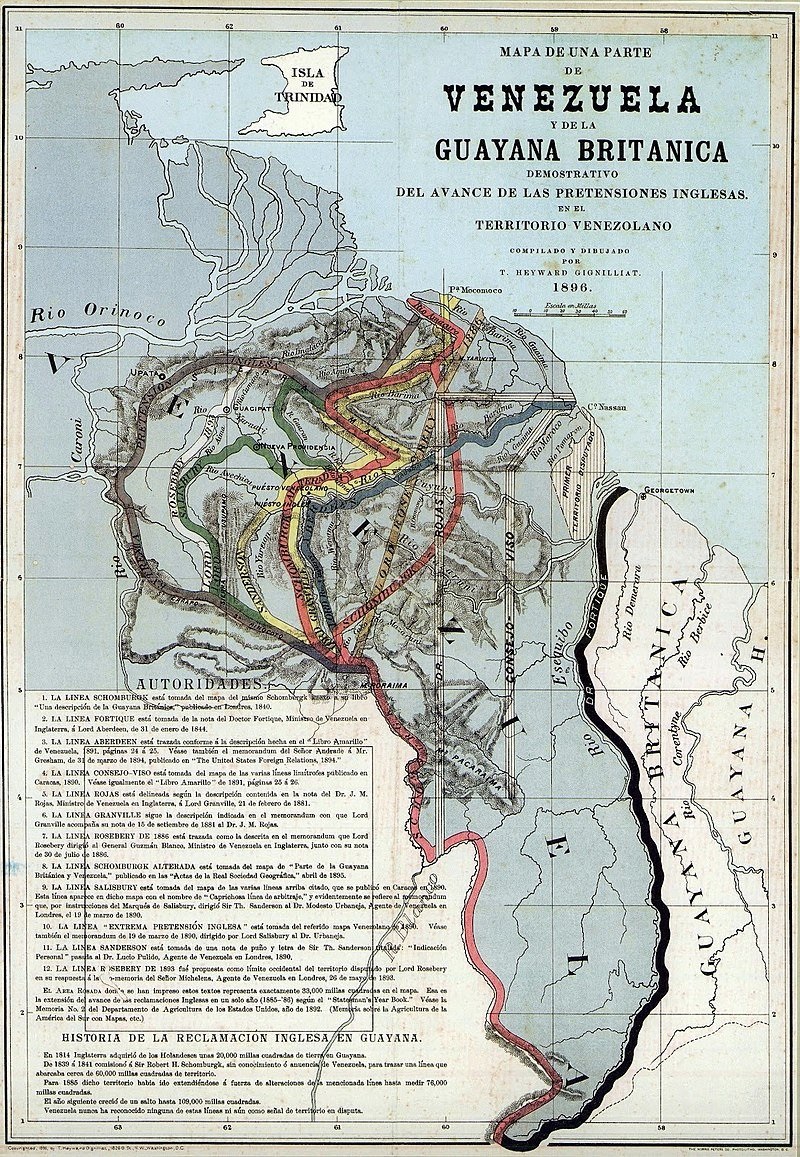

Venezuela questioned the findings of the "Schomburgk Line", believing that this way Great Britain illegally acquired an area of approximately 80,000 km2 of the Esequibo province which Venezuela claimed. In 1886, both countries broke off diplomatic relations, and Venezuela asked the United States for protection.

In 1895, the so-called Venezuelan crisis erupted – the circles lobbying for the country managed to convince the United States that an unsettled territorial dispute between Great Britain and a South American state was a threat to the Monroe Doctrine (i.e. the principle of non-interference by European states in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere).

The American intervention led to an arbitration agreement between the United States and the United Kingdom in 1896, with a rather curious construction, as Venezuela was not a party to the agreement.

Great resistance from this country resulted in the Washington Treaty of 1897 drawing up an arbitration agreement between Great Britain and Venezuela.

The agreement specified the choice of arbitrators: two US Supreme Court judges (Fuller and Brewer) on the Venezuelan side, two British arbitrators, and Fyodor Martens (the author of the famous Martens clause) from Russia was the fifth arbitrator.

It should be noted that the United States was de facto a party to the trial, although de jure the case concerned Venezuela.

The British believed that the Spaniards had never effectively acquired ownership of the disputed territory and, therefore, it was terra nullius, subject to appropriation

Judgement of the Arbitral Tribunal

The Court issued a judgment in 1899 in which, without justification, it granted almost the entire disputed area (and all the gold mines) to Great Britain, setting the border between British Guiana and Venezuela on the Schomburgk Line, which was very favourable to the British. Venezuela was bitter about the outcome of the arbitration but accepted it.

Open letters 50 years after the tribunal trial

This state of affairs lasted until 1949, when the Venezuelan government received letters from one of the Venezuelan government's plenipotentiaries (Mallet-Prevost) from the 1899 trial, which could only be opened after his death. These letters claimed that there was a backroom deal between Russia and the UK over the verdict, with Fyodor Martens behind it. Martens indicated to the US arbitrators that they would either agree to award the disputed area 90% to the UK,

or they would be outvoted 3-2 and then Venezuela would not even receive 10% of the disputed territory. The US arbitrators agreed to such a deal, considering it a better option than being outvoted.

In 1962, as an aftermath of the letters being read out, Venezuela reported at the UN that it had been forced to accept the 1897 Treaty, which was unfavourable to it. It was argued that Venezuela was deprived of the right to appoint its own arbitrators and to adopt as a rule of adjudication a period of 50 years of incumbency (obviously favouring Britain).

Independent Guyana and the continuation of the dispute

Guyana gained independence from the United Kingdom i 1970, within the limits set by the 1899 ruling. From the beginning, relations between Venezuela and Guyana were bad, with Caracas torpedoing Guyana's admission to the OAS (Organisation of American States). In 1966, an agreement was adopted in Geneva under which the two countries were to work out a solution to the dispute by peaceful means. Good offices offered by the UN under Art. 33 of the UN Charter did not work.

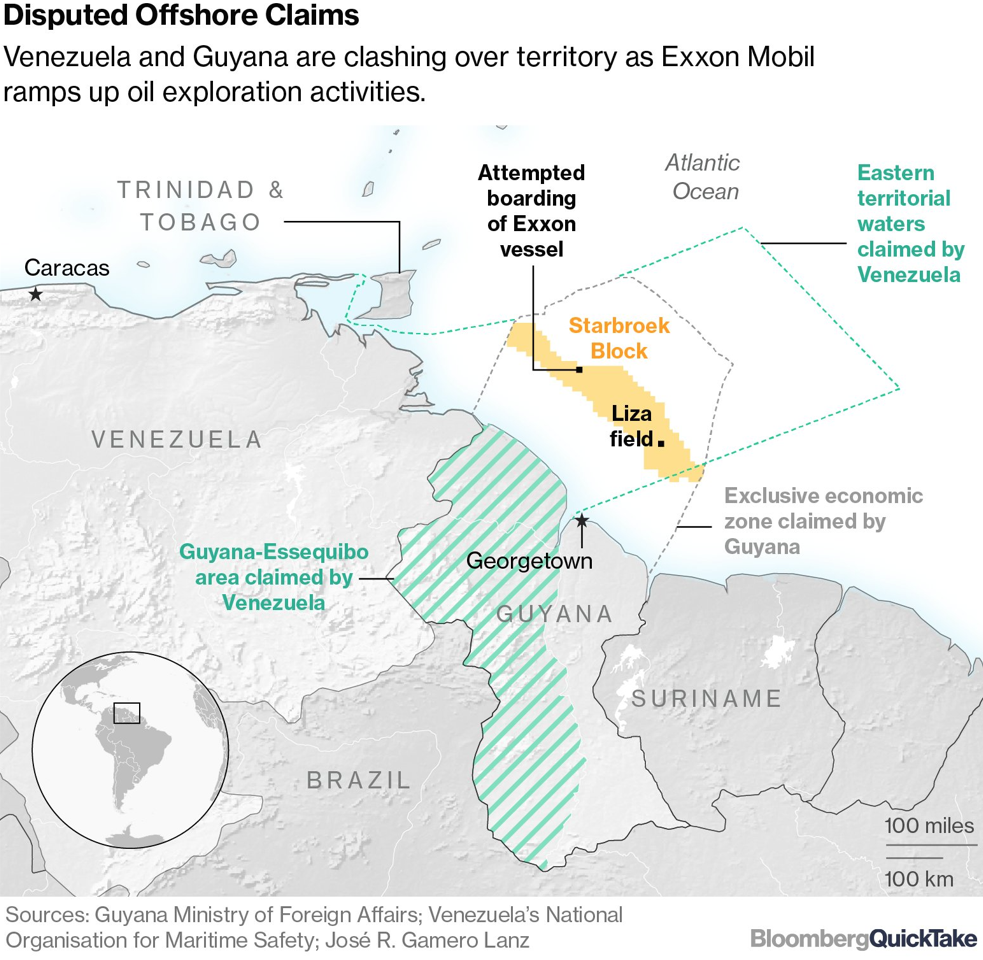

Over the following years, there were demonstrations of force by Venezuela, and even the confiscation of Guyanese ships by the Venezuelan navy as part of the disputed exclusive economic zone.

In 2018, Guyana filed a lawsuit against Venezuela in the International Court of Justice, requesting that the Court declare the 1899 arbitration award valid and final.

This coincided with the UN Secretary-General's statement that the UN's nearly 50 years of good offices could no longer make any progress. The ICJ's jurisdiction stemmed from the 1966 Geneva Agreement between the parties to the dispute, under which the UN Secretary-General, having exhausted alternatives, could indicate the need to settle the dispute by judicial means.

In 2020, the ICJ stated that it had jurisdiction over the case. Venezuela considers that the 1966 agreements invalidate the 1899 judgment and believes that the principle of uti possitedis, or 'as it was let it continue', should apply.

The ICJ ruled that Venezuela should refrain from any actions that might change the status of the disputed area on 1 December 2023.

A referendum to determine the territory of a foreign state was held in Venezuela on 3 December 2023. To my surprise, the referendum asked questions suitable for an international law test.

However, question number 5 is actually the most serious one: the government in Venezuela is actually asking its citizens whether they support the annexation of Esequiba.

Conclusion

I consider the referendum to be of no international legal significance whatsoever, and indeed conclude that the very fact of holding it is a violation of the principle of non-intervention (Article 2(7) of the CFC) in matters reserved for the exclusive competence of one state.

Question 5 is a question about annexing the territory of another state, an action that violates sovereignty and territorial integrity. If Venezuela launches any military demonstration in connection to this referendum, we will be dangerously close to the threshold of the prohibition on the use of force.

The above text was originally published on website X.

Source: Dr Mateusz Piątkowski (Department of Public International Law and International Relations, Faculty of Law and Administration)

Edit: Michał Gruda (Communications and PR Centre, University of Lodz)

The mission of the University of Lodz is to conduct reliable research and actively disseminate facts and research results so as to wisely educate future generations, be useful to society and courageously respond to the challenges of the modern world. Scientific excellence is always our best compass. Our values include: courage, curiosity, commitment, cooperation and respect.